Flemish Lace History

Delicate and exquisite Flemish lace is an essential attribute of royalty. Flanders has always been renowned for its lace, rivaling Italy in its craftsmanship. The secret of creating these intricate laceworks goes beyond the nimble fingers of lacemakers—Flemish artisans cultivated flax suitable for lace production and possessed the technology to produce ultra-thin linen thread.

During the Middle Ages, the borders of Flanders were constantly contested in wars due to its coveted status. By the 14th century, Flanders had become a center of art in Europe, where great artists and skilled craftsmen flourished. In the 15th century, Flanders was conquered by the Duchy of Burgundy, followed by the Habsburgs. The western part of the country was claimed by the French under Francis I. Officially, Flanders ceased to exist as a sovereign state after the French annexation of the Austrian Netherlands in 1795.

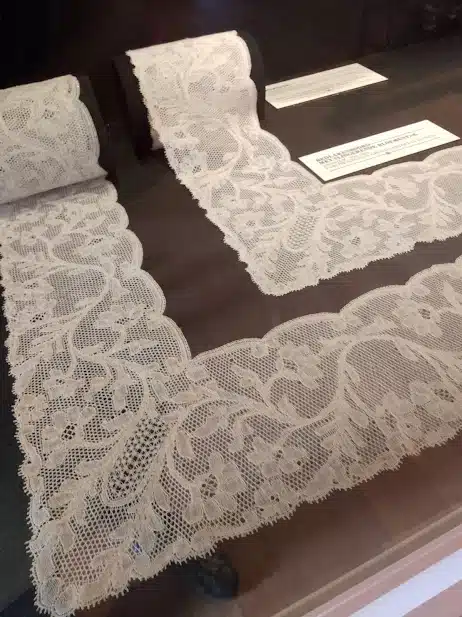

The craft of lace-making still exists today, although the techniques used in the 17th century have been largely lost. Flemish lace varied in ornamentation and pattern, depending on the province of its origin. The lace was named after the towns where it was produced, such as Mechelen, Duchesse, Bruges, Brabant, and Binche.

Examples of lace usage in modern history:

- Princess Victoria of Sweden’s Wedding: Princess Victoria, the heir apparent to the Swedish throne, married her former personal trainer, Daniel Westling. Her veil was made of richly decorated Brussels lace of Queen Sofia’s Lace Veil. Queen Sofia of Sweden wore a lace veil made of Brussels lace at her wedding to King Carl XVI Gustaf in 1976. The same veil had been worn by the mother of the crown princess, Queen Silvia, during her marriage to King Carl XVI Gustaf. Queen Sofia later gave the veil to her younger son, Prince Eugen. This Brussels lace veil is now housed in the National Museum of American History.

- Grace Kelly’s Wedding Dress: American actress Grace Kelly wore Brussels lace on her wedding dress when she married Rainier Louis Henri Maxence Bertrand Grimaldi, the 13th Prince of Monaco from the House of Grimaldi, in Monaco in 1956. The dress, designed by Helen Rose, an Oscar-winning costume designer, was a gift from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a gesture of successful collaboration. The dress, featuring Brussels lace that was 125 years old at the time of purchase, was considered one of the most expensive in the world, estimated at $300,000.

- Princess Stephanie of Belgium’s Lace Veil: Another notable example of “royal” Brussels lace is the veil worn by Princess Stephanie of Belgium at her wedding to Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary in 1881. However, this marriage marked the beginning of the decline of the Habsburg Empire. Many years later, Stephanie was forced to sell the imperial veil of the Habsburgs to support herself. The masterpiece is now displayed at the National Museum of American History.

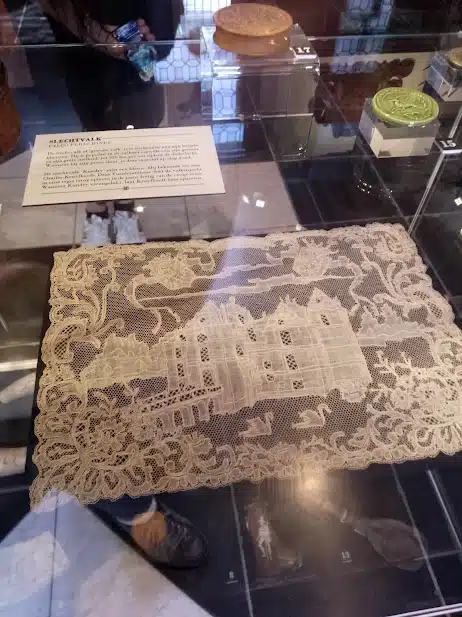

Brussels lace is characterized by separate elements that are later connected on a unified background. It is considered the most expensive type of lace, and possession of Brussels lace has long been a sign of elitism. During the peak of the lace craze, Flemish lace, particularly Brussels lace, was prohibited from being imported into England. However, the demand for it was enormous, leading to illegal smuggling. This lace became known as “anglaise” or “English lace.”

Mechelen lace, also known as Malines lace, is a bobbin lace made by winding threads on bobbins. The finished work is secured with pins on a cushion. Malines lace is known for its floral motifs and a background of small hexagons. It was often used for cuffs and jabots. Towards the end of the 18th century, Mechelen lace became more transparent, lightweight, and airy. The delicate floral ornamentation was placed on a tulle background with small cells. It adorned batiste and muslin dresses. Similar lace was also produced in Antwerp and Turnhout, but Antwerp lace was coarser in comparison.

Binche lace shares similarities in terms of netting and ornamentation with Mechelen lace. A distinctive feature of these Flemish lace variations is the rocaille ornament and a dense net background. In the 17th century, the town of Binche in Flanders began producing woven lace that lacked relief but was extremely delicate. The tight intertwining of threads formed intricate patterns, while the background resembled a dense, patterned net, reminiscent of the shimmering of snowflakes (fond de neige).

Bruges Lace: In 1717, Bishop Van Susteren of Bruges decided that the less fortunate should have the opportunity to produce lace for the affluent. The Apostolic Sisters took up the cause and successfully organized the production. By 1860, there were over five hundred students, and lace-making became popular. The foundation of Bruges lace consists of an endless strip of lace, interconnected to form an ornamental pattern. Up to 700 bobbins can be used for its production.

Flandrians lace bears a resemblance to Vologda lace in appearance. It’s logical. In 1725, by order of Peter the Great, lace-making nuns were brought from Brabant to teach girls from the Novodevichy Convent how to make Dutch lace.

Brabant Lace: Brabant lace gained popularity at the royal courts of France and England. Its foundation consists of hexagonal loops. The delicacy of Brabant lace was achieved through the use of locally sourced flax for the linen thread. The lace made from such linen had a gentle pink tone. In the 1830s, machine-made tulle nearly extinguished this unique craft. Lace made from cotton threads pales in comparison to the softness, lightness, and elasticity of Flemish linen lace.

These different variations of Flemish lace represent the rich heritage and craftsmanship of Flanders. Although the lace industry has changed over time, the legacy and artistry continue to be treasured and celebrated.

Writer Rovendo

Original content license agreement Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license